Matt Dennis

Catalogue essay for BLACK SEVERN ANGEL Pete Hoida paintings 1993 - 2022 Museum in the Park, Stroud 2024

I never had the pleasure of meeting Pete Hoida. I came close: we’d emailed back and forth, agreeing that I would

visit him in Stroud, and that we would stand in front of the work and talk about it, and film the proceedings; but

first the pandemic and then his failing health, forced a postponement, and then his passing in March 2023 made that

postponement permanent.

In February of this year, Pete’s wife, Caroline, rescued my planned visit from oblivion. She was laying the

groundwork for what would become ‘Black Severn Angel’, and would I care to write something for the catalogue? I

came to the house, and we went together into the garden studio, where stacked paintings leaned against the walls,

and got to work.

Lifting the long paintings off the stacks, their backs to us, and walking them through a half-circle to lean

or hang, image outwards, on the viewing wall, felt like pushing again and again through a revolving door between

worlds a canvas-thickness apart: the one all matter-of-factness, all staple-studded stretcher bars and titles scrawled

in charcoal on yellowy-white cotton duck, the other all surprise, and then recognition, and then delight. Over and

over, throughout the day, until there was nothing more to look at...

What to paint? What to put inside that dauntingly blank rectangle? Every abstract painter has to find for

themselves what critic Benjamin Buchloh has termed ‘a matrix’: that is, a set of parameters - formal or conceptual -

that restrict what is permissible, yet in so doing, provide the artist with a field of possibilities within which to work.

For Pete Hoida, first coming to abstraction at the end of the sixties, his matrix of choice was the preoccupations of late

modernism: its insistence on colour as the principal agent of a painting’s formal construction; its rejection of any form of

illusionism, or of modelling in light and shade, or of any suggestion of deep, recessive space; its recognition of the need

for a painting’s design to function, to borrow Alan Gouk’s memorable description, as a ‘taut membrane’ from edge to edge.

This is where Hoida started from: and we might understand his whole project in painting as, in one sense, a long and dogged

exploration of just how much that taut membrane could take before it slackened or snapped.

Tempting as it can sometimes be to find the life within the work - to see scudding clouds over the Severn Estuary in the shifting

horizontals of Tramline, Marshelder, or the soot-blackened wall of a Birkenhead church in the fretted surface

of Language in Another Register - it should be remembered that, for any artist deserving of the title, the work is the life, or in many

ways the best part of it; and that the work pushes out into the world harder than the world pushes in. A painting such as Black Severn Angel -

over two and a half metres long, and four times wider than its height - overpowers with its lateral spread, lining up its jostling forms

in a row; whilst Sobhrach - similarly proportioned, and only marginally less wide - insists on the tightly-packed, horizontal back-and-forth

of its earth tones and muddied primaries. The power of these paintings resides not in resemblances, but in the manner in which they address,

and resolve, questions peculiar to abstraction.

Modernism was supposed to have freed us from the three-tiered spatial architecture of the Western tradition in painting: the here,

the near and the far, most easily seen when most blatant and ‘stagey’, or when already halfway to parody, as they are in Manet’s ‘Dejeuner

sur l’herbe’, with its picnic basket spilling at our feet, its clothed and naked picnickers beyond, and beyond them, its view through

foliage to meadows and skyline. In abstraction, the three tiers have been collapsed down into a distance-denying coloured frieze; but

nevertheless, old viewing habits die hard, and it has proved impossible to stand before even the most resolutely abstract painting and

prevent the eye from probing the surface for foreground, middle ground and distance. Hoida’s long horizontals thwart this tendency by

being too elongated to have three tiers imagined onto them, functioning instead as single tiers, freed from the expectation of bodying

forth spatial recession, free to play host to overlapping and interlocking bands of brushed colour-as-colour, rather than colour-as-space;

whilst his tall, narrow vertical paintings sidestep depicted depth through the bare fact of their format’s evocation of a standing form -

a reading reinforced in Funny Valentine IV and Off-kilter Persimmon and Moon by their

totem-like stacking of elements.

Is this all sounding too formalist, too dry, too caught up in the mechanics of a certain kind of abstract art-making? It shouldn’t be.

Hoida’s paintings are saturated with emotion; but it is emotion embodied in the material, and held there by his extraordinary, unwavering

attention to that material’s every nuance. Hoida himself was emphatic on what Mel Gooding described as the ‘primary dynamic’ of his painting,

the making of the object itself: speaking on film of a painting in progress, he was at pains to insist that ‘It’s not a landscape, it’s not a

picture of something; it’s an artefact created on the rectangle.’

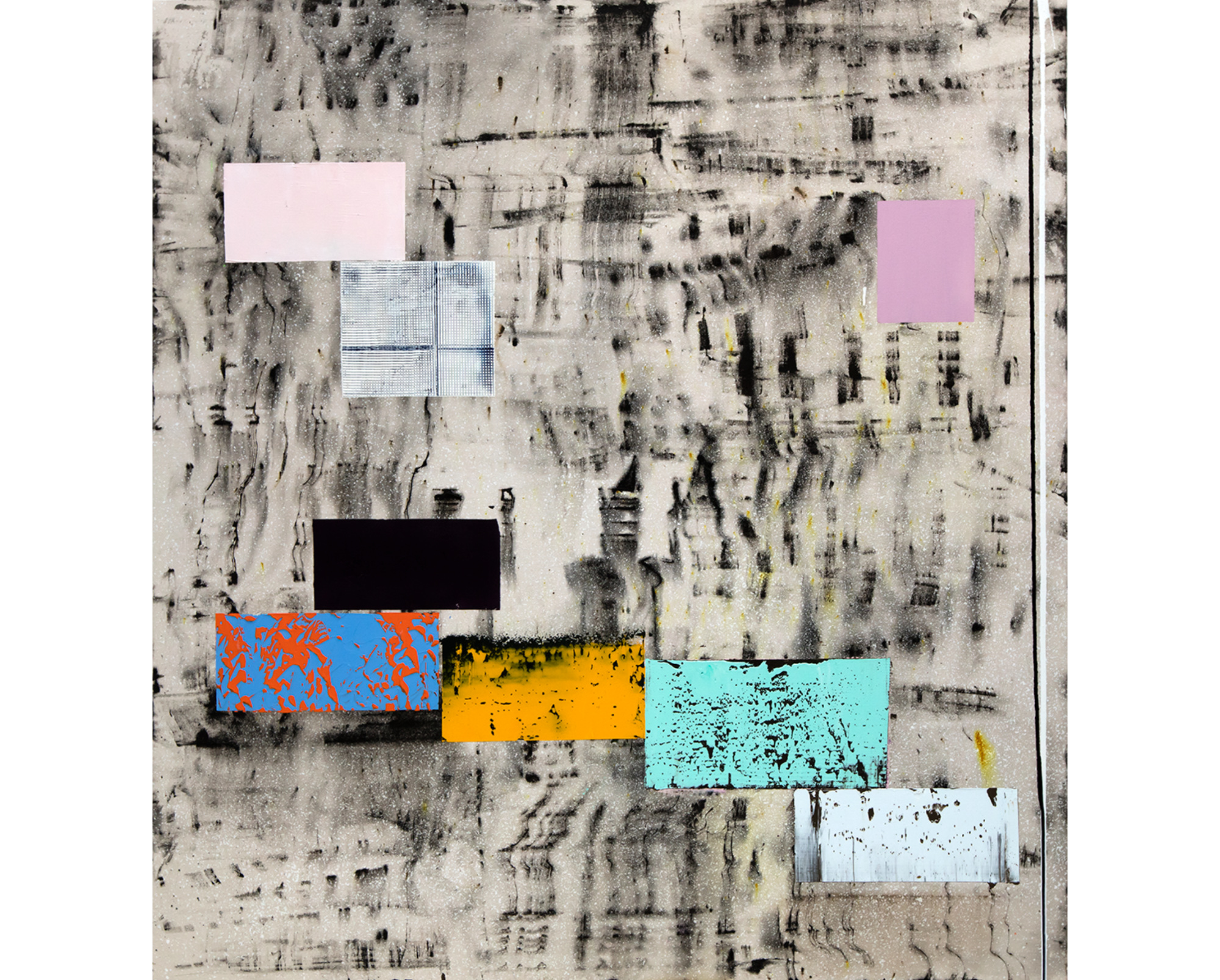

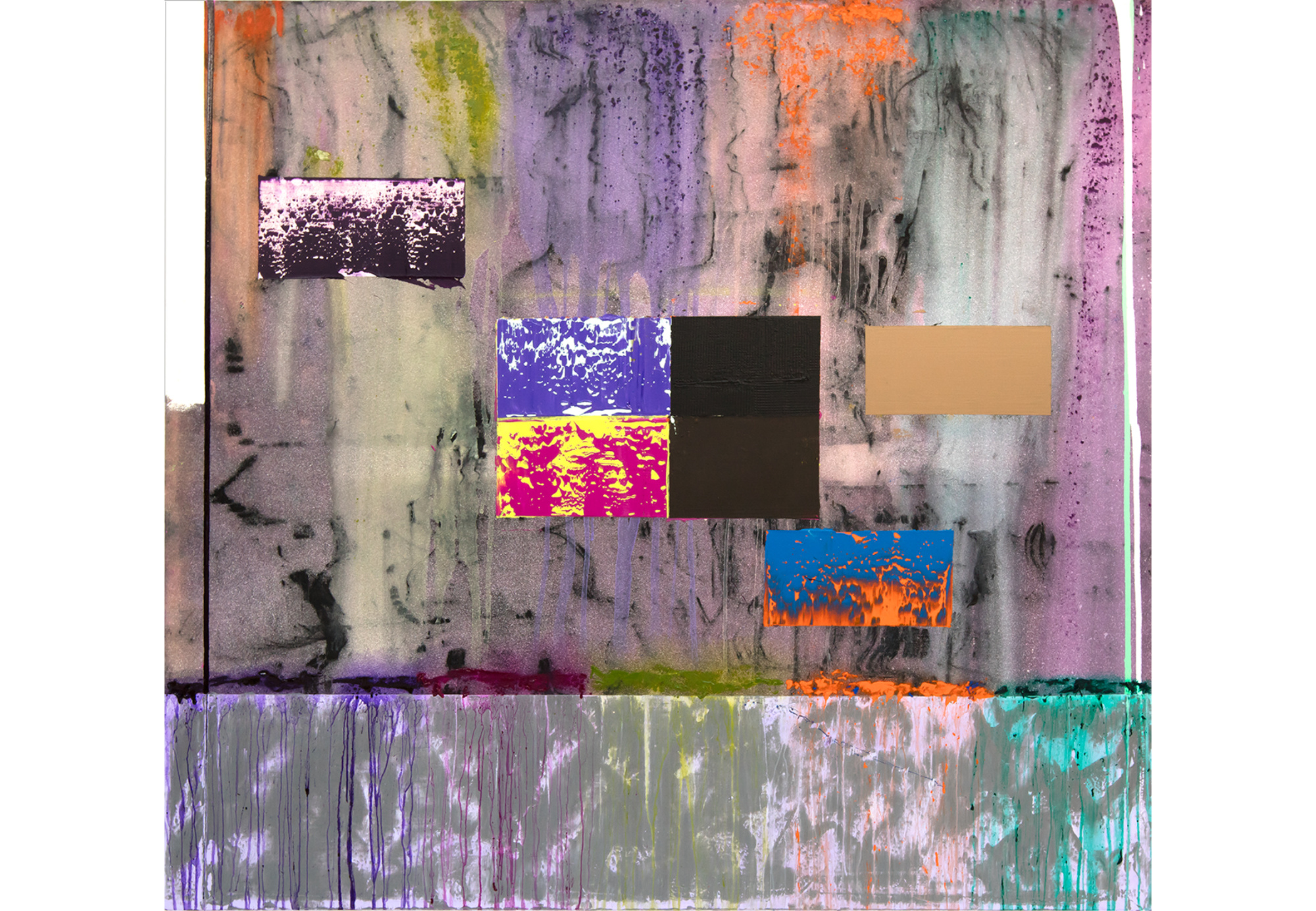

Artefacts created on the rectangle: the paintings of what proved to be Hoida’s last phase of work are that, without a doubt. Rectangles abound: no longer

painted freehand in flowing strokes, but hard-edged, palette-knifed, drifting singly or in clusters over the brush-scrubbed and stained grounds, or locking

together like masonry. Some have been rendered in a single, unmodulated hue; some have been left incomplete, with tattered edges ebbing away into the

atmosphere; some have had painted papers pressed into their wet surfaces and peeled away; some have been spattered by a brush or had paint dripped or

poured downwards over them. It’s as if, by gathering so much painterly incident up inside the confines of the blocks, that whatever has remained unenclosed

in the surrounding field has been left to fend for itself, and an anarchic free-for-all has broken out: in ‘Stroud Standard Time’ the brushy brown-black

field has coalesced into glyphs and pictograms that seem to be cartoonishly mimicking the stacked blocks; what has elsewhere been background (the brushmarks)

has here become image, and what has been image elsewhere (the blocks) now feels like a selection of swatches of possible backgrounds, a ‘mood board’, even,

as if the painting were insisting, ‘choose one’; whilst in ‘Turing Speaks Today’ there is something almost feral in the frantic smearings of swirling, cursive,

violet strokes. In painting after painting, Hoida's forms prod and probe, as if searching for weak spots to push through and drag the image into depth; and

yet the 'taut membrane' remains intact, thanks to his unerring instinct for the precise point at which to pull back, and let the painting be. Decorum is

maitained, but only just.

By taking the tropes of a certain strain of painterly abstraction - the rectilinear slab of paint atop a stained field - and playing freely with them,

and having them proliferate and come together in startling combinations, Hoida was able to generate a new kind of space in his painting; not so much by

the ‘push-pull’ of coloured rectangles advancing and receding (the blocks stay obstinately up on the surface, in almost every case) but

through sensations evoked by their clustering, their overlapping, and their lateral drift across activated grounds.

‘Madame Butterfly’ is surely the masterpiece of Hoida’s late style: the columns of spectral coloured staining over grey, their bandwidths moving in and out of phase

with the descending or ascending blocks of mottled paint as they pour down onto the ‘shelf’ that spans the base of the canvas, the light pouring out of the superimposed

magenta and yellow, the heat radiating from the superimposed orange and blue; all of this richness and strangeness points the way that he was going, and would have

continued travelling, had he been granted more time in which to paint. There is, for us, a frustration borne of knowing that we will not be offered anything more

by Pete Hoida. We will have to settle for what we already have. But that, happily, is more than enough.

Matt Dennis, April 2024